Late in 2007, Sean Penn’s film

Into the Wild stirred renewed interest in the story of Christopher J. McCandless, the young man on whom the film, and Jon Krakauer’s book of the same name, focuses. It’s been over fifteen years since the young man walked out of civilization and into the wild, and the story of what happened to him remains in the public consciousness. But the three depictions of him--the original 1993 magazine article by Krakauer, the resultant book (1996), and then the film--are fundamentally different.

A graduate of Emory, McCandless tramped across the nation for the better part of two years before thumbing his way to Alaska to embark on a solo, natural “odyssey” of his own devising. If you’ve never heard of him, the facts are these: McCandless hunted and gathered in the solitude of the Last Frontier for more than a hundred days, but eventually starved to death at the age of 24, and lay dead in an abandoned bus in the Alaskan bush. Moose hunters found his body in September 1992.

This

PDXWD writer came to McCandless unchronologically, seeing the film first, then reading the article, and finally the book—a circuitous route, true to McCandless’ style. The question that remained after all this exposure to the story, however, was: What are we supposed to make of Chris McCandless and the wide range of responses—from anger to understanding—his adventures have incited from readers and viewers?

One of the main problems in discussing McCandless is that we are apt to interpret his actions before we know much about him, a situation that makes it difficult to describe what he did without using such words as “sad,” “tragic,” “unwise” or even, as some people do, “stupid.” Both Penn's movie and Krakauer's book make compelling interpretations of McCandless’s ill-fated sojourn (though perhaps McCandless wouldn’t have called it “ill-fated” at all), but they also succumb, inevitably, to the very impulses they warn readers against: Krakauer and Penn cannot help but want you to agree with their visions of McCandless.

The

film, for instance, features carefully-timed Eddie Vedder tunes that jibe with McCandless’ letters being written over the action. I wished many times that more trust were put in cinematography and the story itself, rather than elaborately-planned pathos--the film lacks important silences and is worse because of it. Penn’s adaptation shines a sympathetic, if not overtly heroic, light on McCandless and his trip, romanticizing the man's hopes and dreams. Penn presents an homage to the man, but the McCandless character is rarely allowed to just exist onscreen, because McCandless the man is forever refracted through Penn’s vision of him.

As a book,

Into the Wild is vigilant in continually paying respect to McCandless, never allowing the young man to be boiled down completely. Krakauer does not hide that the impetus behind turning “Death of an Innocent” into a book was in part to rescue McCandless from those who called him dumb and ill-equipped after the article first appeared. (Many Alaskans lambasted the magazine for publishing a piece that would encourage more "crazies" to trek to and through their state.)

Rather than convince us of McCandless’s bravery with catchy guitar riffs or extended comparisons to visionaries of the past, however, the film and book might have allowed us to decide on our own whether what McCandless did was courageous, ludicrous, or both. Though those second and third options are certainly plausible, the overwhelming evidence the film and book present is that McCandless rests safely in sainthood. Both seem to imply that they don’t want McCandless maliciously interpreted, though to graciously interpret him is okay.

First published in

Outside in 1993, Krakauer's “Death of an Innocent” (the original article that he expanded to create the longer, more robust

Into the Wild) was a finalist for a National Magazine Award, and is still available in

Outside’s

online archive. McCandless’ actions and inspirations were too complex and unconventional to be reduced to something simple, and lost in the film and book are the raw, uninterpreted facts of the original article’s reporting, and its unprocessed details that allow the reader to make of the situation what she or he will.

For me, therefore, these facts themselves—left alone, as they are in the magazine article, without elaboration or lengthy explanation—are the most compelling, because it seems that's what McCandless himself would have wanted. Indeed, the young man desired only to live as fully as possible without the burdens and layers of meaning and symbolism and interpretation heaped on him or what he did.

Late in 2007, Sean Penn’s film Into the Wild stirred renewed interest in the story of Christopher J. McCandless, the young man on whom the film, and Jon Krakauer’s book of the same name, focuses. It’s been over fifteen years since the young man walked out of civilization and into the wild, and the story of what happened to him remains in the public consciousness. But the three depictions of him--the original 1993 magazine article by Krakauer, the resultant book (1996), and then the film--are fundamentally different.

Late in 2007, Sean Penn’s film Into the Wild stirred renewed interest in the story of Christopher J. McCandless, the young man on whom the film, and Jon Krakauer’s book of the same name, focuses. It’s been over fifteen years since the young man walked out of civilization and into the wild, and the story of what happened to him remains in the public consciousness. But the three depictions of him--the original 1993 magazine article by Krakauer, the resultant book (1996), and then the film--are fundamentally different.

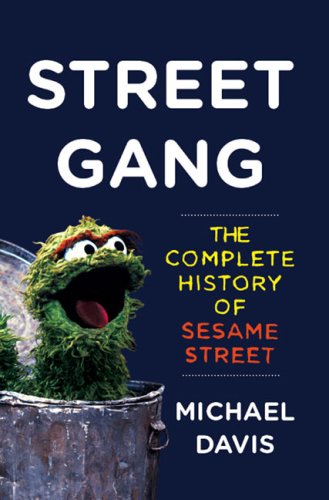

One of this reviewer's earliest television memories is watching the upbeat intro to Sesame Street in a state of rapt attention. In the version I remember (aired in the early 1980s), Big Bird and pals run up and over a park hill and through the city as they ask in song, “Can you tell me how to get, how to get to Sesame Street?” And though I didn’t realize it until looking at Street Gang, Michael Davis's newly-released history of Sesame Street, a lot of what I learned about people, math, spelling, and society came from that show. But of all things on which to write a history right now, why Sesame Street?

One of this reviewer's earliest television memories is watching the upbeat intro to Sesame Street in a state of rapt attention. In the version I remember (aired in the early 1980s), Big Bird and pals run up and over a park hill and through the city as they ask in song, “Can you tell me how to get, how to get to Sesame Street?” And though I didn’t realize it until looking at Street Gang, Michael Davis's newly-released history of Sesame Street, a lot of what I learned about people, math, spelling, and society came from that show. But of all things on which to write a history right now, why Sesame Street? never sat still for even a moment. They're continually asking what’s in the modern zeitgeist? What do children need now?”

never sat still for even a moment. They're continually asking what’s in the modern zeitgeist? What do children need now?”